How do animals survive winter?

How do animals survive winter? The question might seem trivial: we all know that some animals hibernate while others move in search of warmer climates; reality is, as always, more intricate, bizarre, and interesting.

Some strategies for winter survival within the animal kingdom have proven so effective that they have been imitated by humans for thousands of years:

Migration: during the hunter-gatherer phase, humans tended to make regular seasonal movements to simplify life during winter;

Adaptation: winter food resources differ from those in summer and are generally scarcer. Our ancestors were forced to change their diet based on the season;

Food reserves: accumulating supplies during warmer seasons allows one to overcome winter while maintaining their spring or summer diet.

Other strategies to overcome winter are directly related to the physiology of certain animals and are hardly replicable by humans. The human body isn’t “wired” for hibernation or diapause and, for obvious reasons, cannot survive within the tiny ecosystem that develops between the snow layer and the ground.

Physical and Behavioral Adaptation

To survive winter, many animals adapt to seasonal weather conditions by changing their diet or using other strategies. Some accumulate fat reserves or develop a thick fur to cope with the low winter temperatures, while others completely change their eating habits based on the limited available resources. Some modify their hunting techniques or change fur color to better blend into their surroundings.

Animals that remain active during winter often possess heat conservation systems: some birds and mammals have an internal mechanism that reduces blood flow to the extremities to minimize heat loss.

The farther north one goes, the longer the winter fur of many mammals tends to become, forming insulating layers of different lengths that trap air heated by body warmth, reducing the risk of hypothermia.

Like humans, the arrival of winter forces many non-hibernating animals to perform some restructuring of their winter dens. Some dig new underground chambers specifically designed to maintain a stable temperature, while others fill their residences with insulating materials like moss or leaves.

The Arctic Fox

The Arctic Fox changes its fur color from brown or gray in the summer to white in the winter for better camouflage in snowy environments. They also store extra fat to survive the cold weather.

Polar Bear

Polar bears accumulate a thick layer of fat, known as blubber, to insulate themselves from the cold. Their fur is also dense and water-repellent, providing additional protection from the icy waters they inhabit.

American Black Bear

In preparation for winter hibernation, black bears undergo hyperphagia, a period of excessive eating to store fat. During hibernation, they rely on their fat reserves for energy.

Chipmunks and Squirrels

These small mammals store food during the warmer months to sustain them through the winter when food is scarce. Some species also grow thicker fur during winter for insulation.

Winter Migration

As temperatures plummet and the landscape begins to transform with the onset of winter frost, certain species embark on extraordinary migrations, driven by an innate instinct to seek refuge in more hospitable environments.

Birds take to the skies in majestic formations, their wings propelling them across vast expanses with unwavering determination. On land, herds of mammals embark on epic treks, forging paths through rugged landscapes and unforgiving wilderness. Along the way, they confront predators, harsh weather, and geographical barriers, their journey a testament to the indomitable spirit of life.

Even beneath the surface of the oceans, marine creatures embark on remarkable migrations, navigating vast expanses in search of food and breeding grounds. From the majestic humpback whales to the graceful sea turtles, these oceanic odysseys span continents and oceans, weaving intricate patterns across the seas.

Animals that migrates for winter

The Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea) is known for having one of the longest migrations of any animal, traveling from its breeding grounds in the Arctic to its wintering grounds in the Antarctic, and vice versa. This round-trip journey can cover a distance of up to 71,000 kilometers (44,000 miles) annually.

Many birds are known for their migrations, such as the Alpine swift (Tachymarptis melba), which finds a mate and breeds in Switzerland during the summer before migrating to West Africa before winter arrives.

Other animals that undertake extensive migrations for winter include certain species of whales, such as the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) and humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), as well as certain species of birds like the bar-tailed godwit (Limosa lapponica).

One of the most spectacular migrations is that of the North American monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus): during the pre-winter migration, over 14 million monarch butterflies migrate to a small valley in Mexico at 3,000 meters above sea level to escape the harsh North American winter.

Among migratory animals are countless species of insects, fish, birds, and mammals. The large mammals of the Serengeti regularly undertake a seasonal migration in search of green pastures and less hot climates: every year, almost 2 million wildebeests move in masses accompanied by hundreds of thousands of gazelles, antelopes, and zebras.

Surviving Winter Hiding Under the Snow

Animals and native humans of temperate regions quickly realized that snow is not just an obstacle but can be used to cope with the harshness of winter frost: snow can be utilized to create an insulating layer, as demonstrated by the igloos of Canadian Inuit.

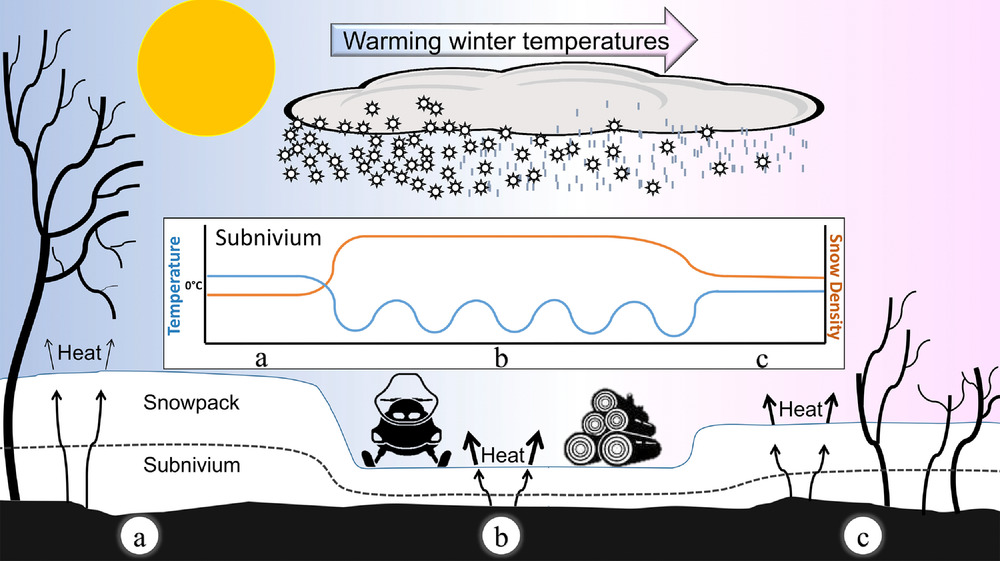

In nature, between the snow and the underlying ground, there exists an actual ecosystem called the subnivium, where invertebrates, small mammals, and even cold-blooded animals such as some reptiles and amphibians survive or thrive.

The subnivium is a relatively warm and isolated microclimate far from being motionless. In addition to small animals hibernating or in torpor, dozens of other species hunt and socialize in this environment protected from winter frost.

Animals that survive in the subnivium

Some medium or small-sized winter predators like owls or foxes can detect the movement of small mammals traveling in the subnivium, while the weasel actively hunts by penetrating this ecosystem and following the scent trails left by its prey.

Voles are well-adapted to surviving beneath the snow. They create elaborate tunnel systems under the snowpack where they can move around, forage for food, and escape from predators. Like voles, shrews can burrow through the snow and find refuge in the subnivium. They are active hunters and feed on insects and other invertebrates they find beneath the snow.

Various species of mice also utilize the subnivium for protection and insulation during the winter months. They may create tunnels or find existing shelter beneath the snow to avoid extreme cold temperatures.

Certain insects such as beetles, ants, and springtails are known to survive in the subnivium. They may hibernate or enter a state of dormancy during the winter, becoming active again when temperatures rise.

Some amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, hibernate beneath the snow during winter, taking advantage of the relatively stable conditions provided by the subnivium. They may find refuge in leaf litter or other organic material beneath the snowpack.

Natural Antifreeze

The wood frog (Rana sylvatica) is common throughout North America. However, the Alaskan subspecies must face much colder temperatures than their southern cousins, especially during winter when the thermometer remains almost constantly below -20°C.

Although wood frogs take refuge in burrows or in the subnivium to survive winter, often this strategy is insufficient to survive the Alaskan frost. Wood frogs are thus forced to use urea and glucose to create a kind of natural antifreeze, enabling these amphibians to survive until spring even if 65% of their body water were to freeze.

Storing Food

This strategy is typically adopted by animals that don’t enter a state of dormancy but survive on food sources no longer available during winter.

The squirrel exemplifies a winter survival strategy honed through evolutionary adaptation. Unlike some animals, squirrels cannot digest cellulose, and thus, they rely heavily on protein, carbohydrates, and fats sourced from acorns, nuts, mushrooms, berries, and fruits.

However, these vital food sources become scarce or entirely unavailable during the colder winter months, presenting a significant challenge for their survival. Unlike animals that hibernate to conserve energy, squirrels remain active throughout the winter season, compelled by their need to sustain themselves.

In preparation for the harsh winter ahead, squirrels exhibit an extraordinary behavior: they diligently gather and store food during the temperate months. This instinctual behavior, known as caching, involves carefully collecting nuts and other food items, then burying them in various locations throughout their territory.

Each cache represents a strategic reserve that sustains the squirrel through the lean winter months when food is scarce. Remarkably, squirrels possess an astonishing memory that allows them to retrieve these hidden caches, even beneath layers of snow, ensuring their survival during the coldest and harshest periods of the year.

Dormant Life

The state of dormancy is a condition in which an animal minimizes all metabolic processes to preserve energy. Dormancy takes various forms, from deep and uninterrupted sleep over entire months to the hibernation of cold-blooded vertebrates.

Hibernation, typical of mammals, involves almost complete immobility and no intake of food or liquids. Heart rate decreases to 1-2 beats per minute, body fat is used to supply the body with nutrients and fluids, and metabolism slows to a fraction of its normal rate.

Depending on the species, animals in hibernation may remain in a deep sleep throughout the entire winter or wake irregularly and then return to sleep (like the brown bear).

Hibernation or overwintering is a mechanism frequently used by cold-blooded vertebrates such as reptiles, amphibians, and fish. It’s not a deep sleep but a prolonged torpor due to a decrease in body temperature.

In the insect world, diapause is common, a type of dormancy typical of some crustaceans and snails as well. During diapause, the animal does not feed and remains completely immobile, a condition similar to the dormancy of mammals but where the body blocks all types of cellular growth.

Animals that sleep, hibernate, brumate or go to diapause during winter

Many bear species, such as black bears and grizzly bears, undergo hibernation during the winter months. They enter a state of reduced metabolic activity, conserving energy until warmer weather returns.

Groundhogs are famous for their behavior on Groundhog Day, where they emerge from hibernation. During winter, they enter a state of hibernation to conserve energy and survive the cold. Some species of chipmunks also hibernate during winter, though their hibernation is not as deep as that of bears. They may wake up occasionally to eat stored food.

In colder climates, hedgehogs undergo hibernation to survive the winter months. They seek out a sheltered spot, such as under leaves or in a nest, and enter a state of torpor.

Many species of bats hibernate during winter when insects, their primary food source, are scarce. They typically seek out caves, mines, or other sheltered locations to roost during this period.

Some snake species, such as garter snakes and timber rattlesnakes, enter a state of brumation during winter. They seek out underground burrows or other sheltered locations and become less active to conserve energy.

Certain turtle species hibernate during the winter, especially those living in colder climates. They may bury themselves in mud at the bottom of ponds or seek out burrows to wait out the cold season.

In regions with cold winters, many toad species undergo a period of dormancy known as hibernation. They may bury themselves in mud or find sheltered spots to survive until spring.