Deep Sea Mysteries: Hunting for Large Unknown Sea Creatures

The ocean, covering about 71% of the Earth’s surface, remains largely unexplored. Its deepest trenches and remote regions have been visited by only a fraction of human eyes and instruments. In these dark and pressurized environments, life has adapted in remarkable ways, often defying our expectations and expanding our understanding of what is possible.

Could there still be unknown large sea creatures lurking in the depths of our seas?

We Know Nothing

Despite our progress in marine exploration, it’s essential to acknowledge the vastness of the oceans and how little of it we have truly explored. The deep-sea environments remain some of the least understood and least explored on the planet.

Only a small fraction of the ocean floor has been mapped with high-resolution detail. The majority of our knowledge comes from shallow coastal areas, leaving much of the deep ocean largely uncharted.

As of the current date in 2024, it’s estimated that we have explored only about 5% of the world’s oceans in terms of mapping and direct observation. This figure might seem surprisingly low, considering the technological advancements we’ve made in marine exploration. However, the ocean’s vastness, depth, and challenging conditions pose significant hurdles to comprehensive exploration.

One of the reasons for this limited exploration is the immense pressure and darkness present in deep-sea environments. The extreme conditions require specialized equipment and vehicles capable of withstanding high pressures and operating in low-light conditions.

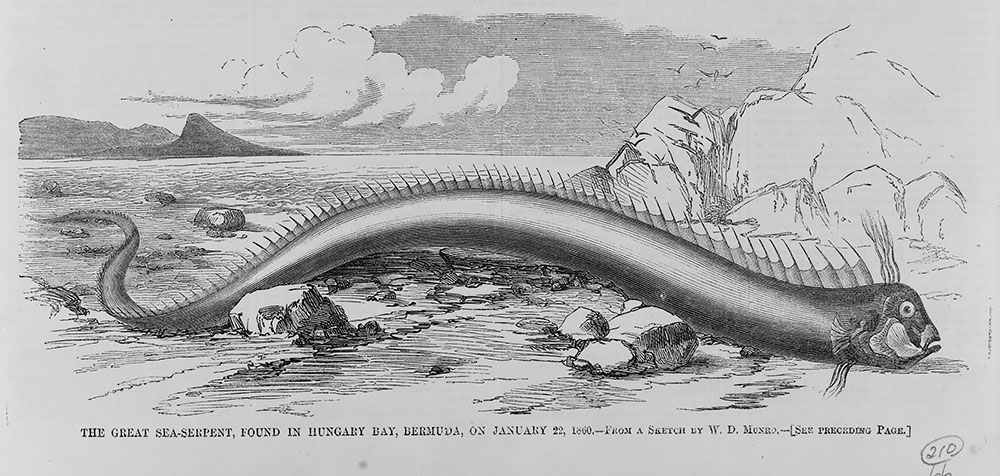

Kraken and Sea Monsters

Throughout human history, the vastness of the oceans has fueled imaginations and inspired tales of mythical monsters and legendary or unknown sea creatures. These stories, often passed down through generations, speak to humanity’s fascination with the unknown and the mysterious depths of the sea.

One of the most iconic mythical creatures is the Kraken, a colossal cephalopod said to dwell in the deep ocean, capable of dragging entire ships to their doom. The Japanese folklore speaks of the Umibōzu, a giant sea spirit resembling a monk that emerges from the depths to capsize ships.

In Greek mythology, Cetus was a sea monster of great size and ferocity. The creature’s appearance and attributes varied across different myths and interpretations, but it was generally depicted as a fearsome sea beast with a monstrous and serpentine form.

While the Kraken, Cetus and Umibōzu are purely products of folklore and imagination, they reflects our fascination with the idea of massive, unseen creatures lurking in the ocean’s depths.

Many sea creatures remain unknown and firmly in the realm of legend, but history has also revealed the existence of real-life giants of the sea. One such example is the legendary giant squid (Architeuthis dux), which was once thought to be a mythical creature due to its elusiveness and rarity in sightings.

Similarly, the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni), another elusive cephalopod species, was confirmed through scientific research, dispelling myths and adding to our understanding of marine biodiversity.

The Colossal Squid

The first confirmed encounter with a colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) occurred in 1925 when the lower beak of one of these elusive creatures was found in the stomach of a sperm whale. However, it wasn’t until decades later that researchers were able to obtain more substantial evidence of its existence.

In 1981, a specimen of the colossal squid was captured off the coast of Antarctica, providing scientists with a rare opportunity to study this mysterious creature up close. The specimen, measuring about 4.2 meters (14 feet) in length, revealed the colossal squid’s unique anatomy, including its large eyes, powerful tentacles, and formidable beak.

Despite this initial discovery, the colossal squid remained elusive, with only a few more specimens being encountered over the following years. It wasn’t until the 21st century that significant advancements in technology and research efforts led to a deeper understanding of this deep-sea giant.

In 2003, a remarkable expedition led by Dr. Steve O’Shea and his team resulted in the capture of a colossal squid specimen off the coast of Antarctica. This specimen, measuring an astounding 4.2 meters (14 feet) in mantle length and weighing over 495 kilograms (1,091 pounds), provided invaluable insights into the biology and behavior of these elusive creatures.

Recent Revelations and New Discoveries

The past few decades have witnessed a surge in groundbreaking discoveries, challenging our preconceived notions about the limits of life in the ocean. One of the most remarkable revelations came with the identification of the Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai) in 2003. This previously unknown species of baleen whale had eluded scientific detection for decades due to its similarities to the closely related Bryde’s whale. However, through meticulous genetic analysis and careful examination of morphological features, researchers were able to confirm its distinctiveness as a separate species.

The Omura’s whale, named after Japanese cetologist Hideo Omura, inhabits tropical and subtropical waters, primarily in the Western Pacific. Its smaller size compared to other baleen whales and unique coloration patterns make it a fascinating subject for study. The discovery of this species highlighted the importance of comprehensive genetic studies in uncovering hidden biodiversity within marine mammal populations.

Hoodwinker Sunfish (Mola tecta)

The story of the hoodwinker sunfish’s revelation begins on a beach near Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2015. It was here that a remarkable find occurred, one that would mark the first identification of a new species of sunfish in 130 years. This momentous discovery was the result of meticulous research and dedication by marine scientist Marianne Nyegaard, who studied ocean sunfish as part of her Ph.D. research.

With a maximum length of approximately 242 cm (7.9 feet) and a weight that can reach up to two tonnes, the hoodwinker sunfish commands attention despite its cryptic nature. Its counter-shaded coloration, darker on the dorsal side and lighter on the ventral side, aids in camouflage and reflects typical adaptations found in many marine species.

The history of sunfish discoveries adds depth to the significance of Mola tecta’s identification. The most commonly known ocean sunfish, Mola mola, was documented in 1758, followed by Mola alexandrini (also known as Mola ramsayi) in 1839. In contrast, Mola tecta remained hidden until 2014 when Japanese researchers, based on genetic information from Australian waters, suspected the existence of a new Mola species.

West African Skate

The Bathyraja hesperafricana, commonly known as the West African Skate, was first documented and described in 1995 in a collaborative effort between marine scientists and research institutions. Its discovery was part of a broader exploration initiative focused on the biodiversity of deep-sea ecosystems, particularly in regions between Mauritania and Gabon.

What sets the Bathyraja hesperafricana apart is its unique morphological features and genetic distinctiveness. This species of skate exhibits a flattened body with enlarged pectoral fins (more that 1 meter long each), typical of rays adapted for bottom-dwelling lifestyles. Its coloration and patterning provide effective camouflage against the sandy and rocky substrates where it is often found.

Genetic analysis conducted on specimens collected during research expeditions revealed significant differences between the Bathyraja hesperafricana and closely related species within the Bathyraja genus. These genetic markers, combined with detailed morphological examinations, confirmed the West African Skate as a distinct and previously unrecognized species.

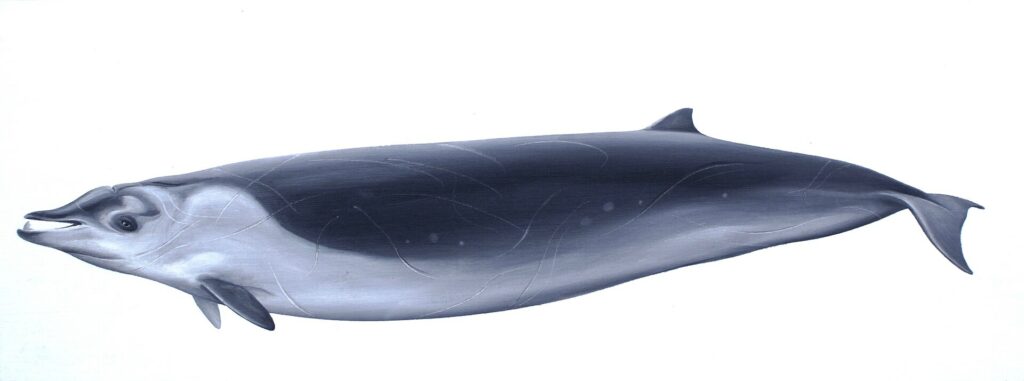

Perrin’s beaked whale

Belonging to the family Ziphiidae, Perrin’s beaked whale is part of the toothed whale suborder and represents just one of over 90 known cetacean species. The Ziphiidae family itself is incredibly diverse, with more than 20 recognized species, making it the second most diverse group among marine mammals.

What sets beaked whales apart is their elusive nature and deep-diving capabilities. These timid creatures are known for their extended dives, sometimes lasting up to two hours, as they forage for squid and deep-sea fish in the ocean’s depths.

In 2002, Dalebout et al. described Perrin’s beaked whale as a new species based on five stranded individuals found along the coast of California between 1975 and 1997. Initially misidentified as other species, these specimens were reexamined, leading to the recognition of a distinct genetic lineage.

As of May 2019, only six Perrin’s beaked whale specimens have ever been examined, further emphasizing the rarity and elusive nature of these creatures. The first two individuals were discovered stranded on the California coast in May 1975, with subsequent findings in 1978, 1979, September 1997 (during a strong El Niño year), and October 2013.

Are there some other large marine animals hiding in the oceans?

Despite significant advances in marine exploration, including the use of advanced sonar technology, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and satellite tracking, there are still vast areas of the ocean that remain unexplored or underexplored.

One of the primary reasons for the possibility of large undiscovered animals hiding in the oceans is the sheer size and depth of these marine environments. The ocean covers more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and reaches depths of over 36,000 feet in places such as the Mariana Trench. These extreme depths, combined with the vast expanses of open water, provide ample hiding places for potential large marine species that have yet to be documented by scientists.

Furthermore, the ocean’s complex ecosystems and food webs offer potential niches for undiscovered creatures to thrive. From deep-sea trenches to remote coastal regions, there are numerous habitats where large animals could remain elusive to human detection.

Sounds From Undiscovered Creatures?

From eerie clicks and whistles to deep rumblings and mysterious pulses, the ocean is alive with a symphony of biological sounds. These sounds, often produced by marine animals for communication, navigation, and hunting, can also include mysterious and unexplained phenomena that challenge our understanding of the marine environment.

One of the most famous examples of a mysterious biological sound in the oceans is known as “The Bloop“. Detected by underwater listening devices called hydrophones in the Pacific Ocean in 1997, The Bloop was an ultra-low-frequency sound of unknown origin. Its characteristics, including its immense volume and frequency range, initially baffled researchers and sparked speculation about its possible source.

The “Julia” sound, named after its detection in the Pacific Ocean in 1999, is another enigmatic noise characterized by its unusual frequency pattern and duration. While it was initially considered a possible biological source, subsequent analysis suggested that it may have been generated by a large iceberg grounding on the seafloor.

The Upsweep is a long-duration, low-frequency sound that was first detected by the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory‘s autonomous hydrophone arrays in August 1991. It is characterized by a series of narrow-band upsweeping sounds that rise and fall in frequency over time. The Upsweep has been recorded seasonally but tends to peak in the spring and fall months.

The Whistle is another enigmatic underwater sound characterized by its distinct whistling or tonal quality. Like the Upsweep, the Whistle has been detected by underwater hydrophones and exhibits unique frequency patterns that set it apart from other marine sounds.